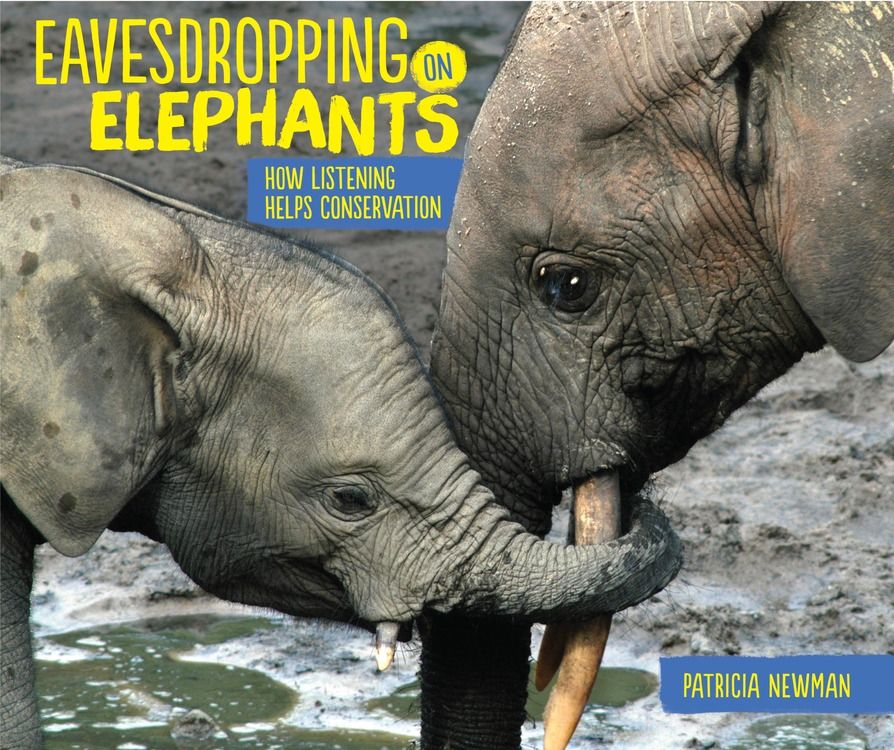

EAVESDROPPING ON ELEPHANTS

Description

Notes

George Aranda Interviews Patricia Newman

#1 – What was the impetus for writing Eavesdropping on Elephants?

Years ago I visited Kenya and came upon an elephant skull. It was huge! Perhaps the elephant died from natural causes or perhaps it was poached. The tusks were gone. Ever since then, I’ve been fascinated by these animals. They remember complicated migration patterns. Matriarchs lead the herd to water and food. Mothers care for their babies with something approaching tenderness. And elephants maintain a complex web of family relationships that rivals humans. They also appear to experience joy and grief.

Another catalyst is the newness of the forest elephant species; most people don’t know anything about them. Unlike savanna elephants who travel in large herds of females, juveniles, and babies, forest elephants travel in small family groups of a few individuals. They meet members of their extended family at forest clearings to catch up on the news. Forest elephants travel miles eating fruit and defecating, which deposits fruit seeds far and wide. Andrea Turkalo, one of the scientists in Eavesdropping on Elephants, calls them the architects of the forest because without them the forest wouldn’t exist.

What’s not to love?

#2 – How did you get involved with the Elephant Listening Project which is central to your book?

My daughter, Elise, used to work for the Elephant Listening Project (ELP) as an undergraduate at Cornell University. Elise sat at a computer with headphones on her ears and catalogued forest sounds, much like the students pictured on page 38 of the book. Her stories about the scientists and their work piqued my interest, and I knew I had to write a book about them one day.

#3 – Your book focuses as much on the way that scientists collect and use data as much as the science facts. Is it important for you to convey the way that scientists do science?

Absolutely! Field scientists are superheroes in my opinion. Their scientific questions often take them to inhospitable places, yet they endure rough conditions to gather precious data. They often have to improvise on the spot when rain, mud, or even a curious elephant interferes and alters their plans. Plus, the whole matrix of scientific thinking–questions, observations, experiments, dialogue, more questions, more observations–appeals to me. The scientific process of discovery can be messy, but it’s also elegant in the way scientists follow facts and form conclusions based on those facts—even if the facts take them in unexpected directions.

#4 – The book focuses on our understanding of the elephants’ calls, in particular the importance of infrasound. What is the importance to understanding their communication? What impact will this knowledge have on us, them and their environment?

The role of infrasound (sounds too low for humans to hear) is much better understood in savanna elephants than forest elephants. ELP conducted some studies that indicate infrasound doesn’t travel nearly as far in the forest. So why have the ability? There must be a reason, and ELP wants to find out. Perhaps infrasound travels farther than we think. Perhaps elephants have “cut off men” (à la baseball) to intercept the infrasound and rebroadcast it so news travels farther. No one knows. And that’s what I love about science. The fact that no one knows makes it worth discovering.

ELP’s acoustic listening devices record all audible forest sound, but no video. As ELP listens to the recordings they can pick out which sounds belong to elephants and determine which parts of the forest they are using. The elephants’ presence or absence in various locations is valuable by itself to assist park managers in making conservation decisions, but ELP wants to go further.

That’s why Katy Payne’s initial collaboration with Andrea Turkalo was so pivotal. Andrea knows thousands of elephants by sight—their habits, their family relationships, their ages. When paired with the acoustic recordings Katy’s team made, they were able to assign meanings to many of the sounds, such as alarm calls, infant distress calls, and greetings. ELP is not yet sure where this “dictionary” aspect will take them, but they hope it will provide even more information to help save forest elephants.

#5 – The book is filled with QR codes which allow access to digital online information such as videos. How did access to this change or influence the way you wrote the book?

Most nonfiction books for kids have back matter that includes further reading and links to online articles or video, but I always wonder if kids pay attention to it.

ELP’s audio and video files bring young readers inside the forest to observe elephants just as the scientists did. That level of cool was too much for me to pass up. I purposely sought out specific elephant communication stories in which I could combine text, images, audio, and video to demonstrate field science for kids. I think it would be fun for kids to watch the videos and jot down observations. What great practice for future scientists, right?

Teachers: The Cornell Lab of Ornithology created a free curriculum guide with several dynamite activities that integrate science and language arts. (How do the Lab of Ornithology and elephants go together? The common link is acoustic listening!)

The Eavesdropping on Elephants Educator’s Guide features ten activities that target national science, math, writing, and art education standards for grades 4-6. http://www.birdsleuth.org/EavesdroppingOnElephants/

Reviews

“Fascinating for earnest conservationists.” – Kirkus Reviews

SLJ:

In forests in the Central African Republic, a symphony of sounds can be heard all around, but the one scientists are concerned with in this book is that of elephants. Telling the story of Katy Payne’s work with elephant sounds and Cornell University’s Elephant Listening Project, Newman gets into the technical aspects of studying elephant sounds and how the project quickly went from being an effort to learn more about pachyderms to one that could help their very survival. With gorgeous full-color photographs, well-defined maps, and insight into the latest technology, this book does an excellent job of transporting readers and providing a clear, multifaceted picture of African forest elephants. Several vignettes in the book feature QR codes that link to video recordings of the sounds that are being discussed, from an elephant hello to a goodbye. The work concludes by emphasizing the importance of conservation: “The more you listen to wildlife, the more your mind opens up to new ideas about why the world is a place worth saving.” The book also includes a bit about the efforts of children to help elephants. VERDICT A great pick for middle school nonfiction collections.–Molly Dettmann, Norman North High School, OK

Booklist:

In 1984, after a 15-year study that involved listening to sounds made by humpback whales, Katy Payne visited the elephants at the Portland, Oregon, zoo and felt a throbbing in the air akin to the sensation of hearing low pipe organ music. She suspected that the elephants were making sounds too deep for human ears to hear. Her experience led to the establishment, 15 years later, of Cornell University’s Elephant Listening Project in the Central African Republic, where Payne and other scientists have been observing forest elephant families, studying their communication, and working to protect them ever since. Besides providing an overview of the project, along with information about the region’s elephants and how they communicate, the text conveys a sense of urgency about the animals’ survival in an era when poaching and forest destruction continue. Among Newman’s cited sources are her interviews with Payne, forest elephant expert Andrea Turkalo, and others active in the project. The many illustrations include color photos of elephants, their habitat, and the researchers. An inviting introduction to biologists at work.— Carolyn Phelan

Kirkus:

The chronological tale of the Elephant Listening Project, from precursory work in 1984 to its ongoing projects—all involving the sounds made by elephants. Although coyly headlining its introduction, chapters, and bibliography with musical terminology, the text is generally straightforward. Readers learn from the introduction (“overture”) that scientists “eavesdrop on endangered African forest elephants not only to figure out what they’re saying but also to save them from extinction.” It goes on to discuss forest elephants as a keystone species. Next, there is a shift to the tales of Katy Payne and Andrea Turkalo, two dedicated researchers whose individual work with elephants and sounds led to the joint venture of the Elephant Listening Project in 1999, including working together at a rainforest research compound in the Central African Republic. Payne, Turkalo, and many of their team members present white, but local Bayaka people were invaluable in roles such as trackers, research assistants, and climbers to place the receivers. (Ground devices fare badly around curious elephants.) Currently, new conservationists, including some Bayaka, continue the work begun by the women. The text abounds with accessible—if sometimes prosaic—explanations of sound, spectrograms, technological advances, and more. Charts, graphs, and colorful photographs supplement the text. The subtitle is a bit misleading; only the fourth and fifth chapters discuss, minimally, “how listening helps conservation.” Grim facts are balanced by hope and faith in the next generation. Fascinating for earnest conservationists. (Nonfiction. 9-14)

Eavesdropping on elephants: How listening helps conservation by Patricia Newman

I’ve really liked Newman’s science titles for middle grade readers in the past and her latest is no exception. Featuring a popular large animal, elephants, this blends science and conservation, mystery and career advice, to give kids a window into the lives of elephants and the scientists who study them.

The book opens with the subsonic rumblings of elephants and the beginning of the Elephant Listening Project in 1984 as biologist Katy Payne transitioned from listening to whales to the seemingly similar sounds of elephants.

Over the years, Katy and other scientists worked to research infrasound, sounds too low for human ears to hear. As readers follow Payne and her assistants on her journey, they’ll learn more about the science behind different types of sound and they’ll meet many different elephants (for fans like me there are bongos too! I love bongos.).

The project encompasses developing technology, encroaching poachers and habitat destruction, and the accumulation and organization of thousands of hours of data as the scientists worked to make sense of the elephants’ sounds. As the years passed, new scientists Liz Rowland and Peter Wrege came on board and the goal of the project began to shift from researching elephant sounds to helping them survive. Then they made a discovery – they could use the sounds of elephants and their scientific interpretation to keep them safe, monitor their health, and advise governments on protecting them.

The book ends with a chapter reflecting on the long history of research into elephant sounds, especially forest elephants as shown in this book, and their current vulnerability, the many challenges they face, and how continued research into infrasound could help. Throughout the book there are QR codes that will allow readers to listen to some of the sounds described. Back matter includes links and suggestions on getting involved, source notes, glossary, bibliography, further reading (books and websites), index, and acknowledgements.

Verdict: For readers who love animals and want to get involved, kids who are fascinated by science, and all those elephant lovers, this is a great book to expand their knowledge and help them learn that there’s a lot more to elephants than just “big.” Recommended.

http://jeanlittlelibrary.blogspot.com/2018/10/eavesdropping-on-elephants-how.html?m=1